Arthouse Summer 2025

Here we go with another film project. I’m calling it Arthouse Summer 2025. Honestly, I think it’s partially a coping mechanism for my family being on holiday without me (and me being home alone), but it’s also to help with the boredom I’m feeling about the films in my local cinema. Superman. Jurassic World Rebirth. F1. Ballerina. I need some cinephile nutrition!

The rules of the game are pretty broad this time around. There’s no quantity target. By summer, I mean now to the end of August. I’m taking arthouse to mean independent films or older films that weren't blockbusters or mainstream. I want to give myself room to explore, a.k.a I’ll know what fits when I see it. Hopefully some themes will emerge.

- Run Lola Run (1998) dir. Tom Tykwer

- Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) dir. Peter Weir

- Morvern Callar (2002) dir. Lynne Ramsay

- PlayTime (1967) dir. Jacques Tati

- Le Samouraï (1967) dir. Jean-Pierre Melville

- Irma Vep (1996) dir. Olivier Assayas

- The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968) dir. Jack Cardiff

- Irréversible (2002) dir. Gaspar Noé

- Caché (2005) dir. Michael Haneke

- Parasite (2019) dir. Bong Joon Ho

- In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai

- Matt and Mara (2024) dir. Kazik Radwanski

July 27 2025, 21:35

Director: Tom Tykwer

Release year: 1998

Lola and Manni are at a relationship crossroads. Manni is trying to make a living doing jobs for a Berlin gangster, Ronnie, and as a test of competence is told to pick up 100,000 DM of diamonds, sell them and bring the money to a rendezvous at midday. He accidentally leaves the bag of cash on a subway train and phones Lola in desperation. She tells him she will fix things, and she’ll meet him with the money he needs—but she only has twenty minutes to somehow make things good.

I saw this in the cinema when it came out and I remember being blown away by the mixture of pulsing techno, Franka Potente running through the streets of Berlin, and the looping narrative. I hadn’t seen anything like it before. I’d forgotten the animation, the philosophical game the film is playing, and the ways character arcs spin in different directions each time Lola’s actions deviate in very small ways.

It’s a beautifully edited film, and it plays with the ideas of free will, destiny, chance, desire and love. Lola’s agency creates the second loop through the timeline, and it’s ambiguous if Lola or Manni create the third, but each time through Lola seems to remember small details from the time before, and her screams at moments of extreme stress certainly bend reality to her will.

The central question of whether the couple can be together is answered when Manni steps up to solve the problem he’s created for himself. There’s an implication from the beginning that he tends to rely on Lola fixing things for him. By the end the lovers are equal.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

July 30 2025, 20:08

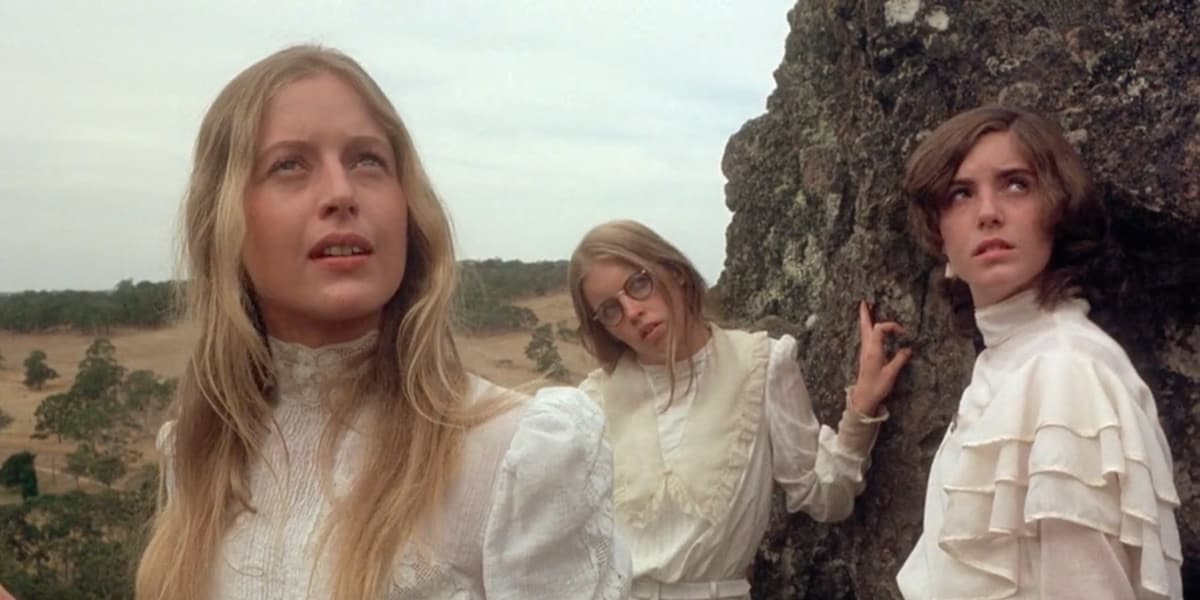

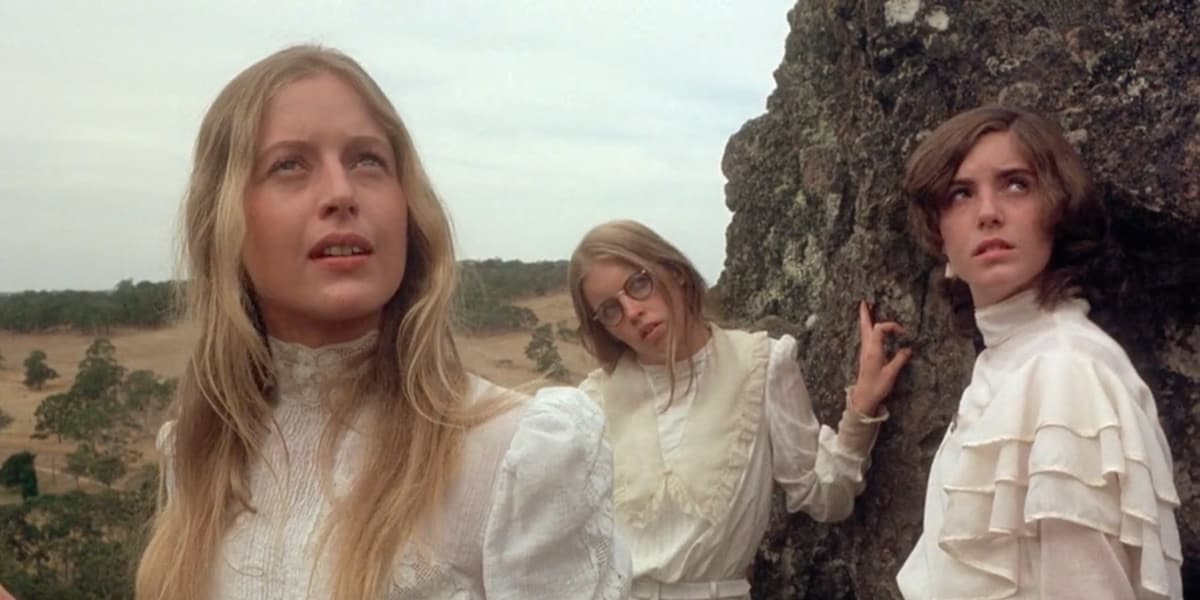

Director: Peter Weir

Release year: 1975

On an outing from their boarding school in the Australian outback, four girls wander around the base of Hanging Rock and are tempted to climb higher. The rocks seem to have ghostly powers and the girls fall asleep in a stone circle near the top. Three of them walk through a gap and disappear. A teacher from the group is also seen walking up to Hanging Rock and also goes missing. The mystery engulfs the school and the local community.

It’s clearly an excellent film. The schoolgirls all give strong performances, the audio is cleverly used to make the viewer feel unsettled watching the corseted, gloved girls in an ancient wilderness teeming with insects and birds, but... I couldn’t get into it. Because I only read the book last week, the faithfulness of the adaptation makes the film seem uninspired. Chunks of dialogue are taken straight from the novel. I can’t seem to see the film on its own merits.

This hasn’t happened to me before. I wrote notes on the book at the weekend on Patreon, and there’s no point in repeating myself. I don’t think the film brings enough new to the story. There’s a stronger focus on the potential lesbian relationships in such a female-centric community, and the friendship between Michael and Albert has gay undertones that I didn’t pick up in the book, but it isn’t enough of a differentiation. A disappointing experience.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 01 2025, 19:21

Director: Lynne Ramsay

Release year: 2002

On Christmas Eve in a Scottish port town, Morvern Callar finds her boyfriend dead on the floor of their flat. In a suicide note, he asks her to send out his unpublished novel to a list of agents. Morvern is trapped in a supermarket job and has no family, so she convinces herself he means for her to post the novel under her own name. She uses the remaining money in his bank account to take her closest friend, Lanna, partying in Spain, and she doesn’t expect the swift response from an agent who loves her book.

I hadn’t seen this film in years, but the novel is one of my favourites. I wanted to repair the damage of not enjoying the film of Picnic at Hanging Rock. Lynne Ramsay and Liana Dognini cowrote the screenplay and, like Picnic, it holds true to the book and sticks closely to the narrative, but for me Morvern Callar is in a different league. Samantha Morton as Morvern and Kathleen McDermott as Lanna are luminous. They shine through the dynamic camerawork, playful use of music (her boyfriend leaves Morvern presents to unwrap that include a Walkman and a mixtape), and the girls’ wickedly infectious personas. It’s gritty and fun and hopeful, and now one of my favourite films.

I think my problems with Picnic at Hanging Rock were that, yes, I don’t particularly like straight period dramas, even clever ones, but more than that, the characters don’t go through any real internal changes. Morvern’s gradual maturing is the beating heart of Morvern Callar.

I love Morvern. She makes what to her are pragmatic decisions around her boyfriend’s death: she accepts his novel as a gift and puts her name to it; she uses his funeral money to go to Spain and disposes of his body; she processes revelations about her closest friend in a stoic and surprising way. And with each decision, she becomes more mature, more outward looking, and begins to imagine a bigger life.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 02 2025, 16:03

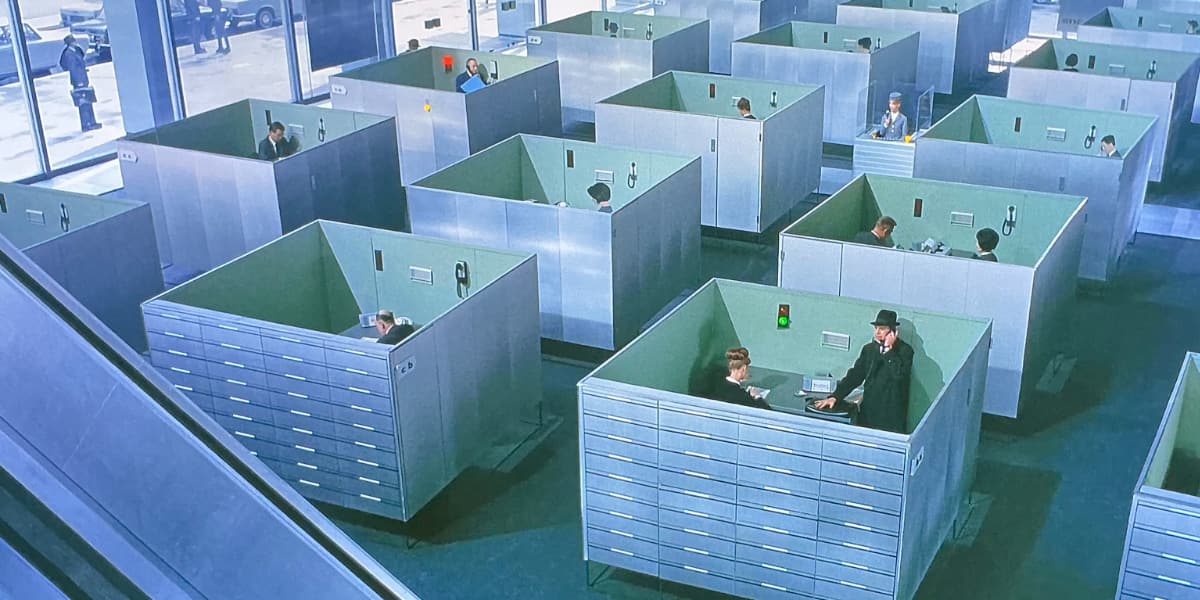

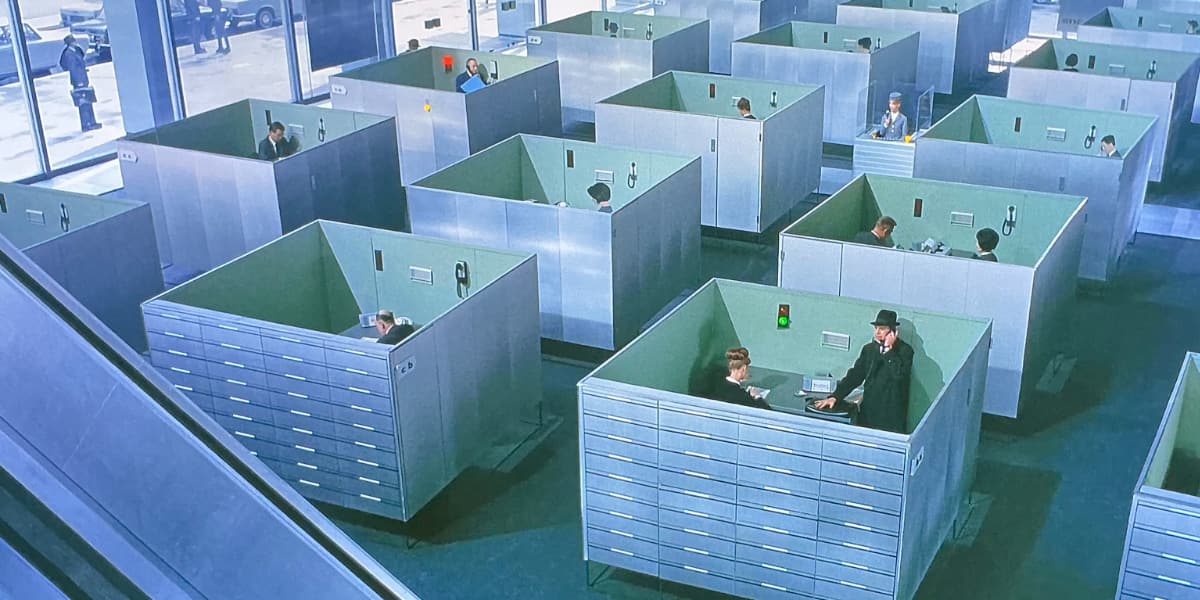

Director: Jacques Tati

Release year: 1967

Monsieur Hulot arrives in the centre of Paris to meet a man about some business, but his attempts to connect are thwarted by the distractions and mechanisms of a modern city. Other people come and go—tourists, businesspeople, tradesmen—culminating in a chaotic dinner at a the opening night of a new restaurant.

There’s no real plot to PlayTime. The city is the main character, a precisely rendered alternate reality where everything runs like a clockwork machine, the buildings full of box-like rooms, and the latest gadgets being presented and sold at all times. Hulot brings a clumsy humanity to the sterile environment, which is like a children’s book version of adult life.

The first half of the film presents a series of comical set pieces, each one bursting with small jokes and events in the foreground and background. It’s impossible to know where to look. I would imagine I would see more on a second viewing. Like the adult world, watching PlayTime is often amusing, but also repetitive and sometimes dull, even with so much going on. It’s like looking at an ever-changing piece of art in a gallery for two hours.

The second hour is mostly set in a newly opened restaurant with many jobs in the building still unfinished. Design mistakes cause staff to trip over, collisions, electrical faults, and all while an increasing number of people flow into the space, until the chaos of humanity overwhelms the architect’s vision, the music gets more raucous, and fun is had in spite of the collapsing dining room. Tati’s message seems to be that for all of modern life’s restrictions, people will find a way to connect and have fun.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 03 2025, 16:44

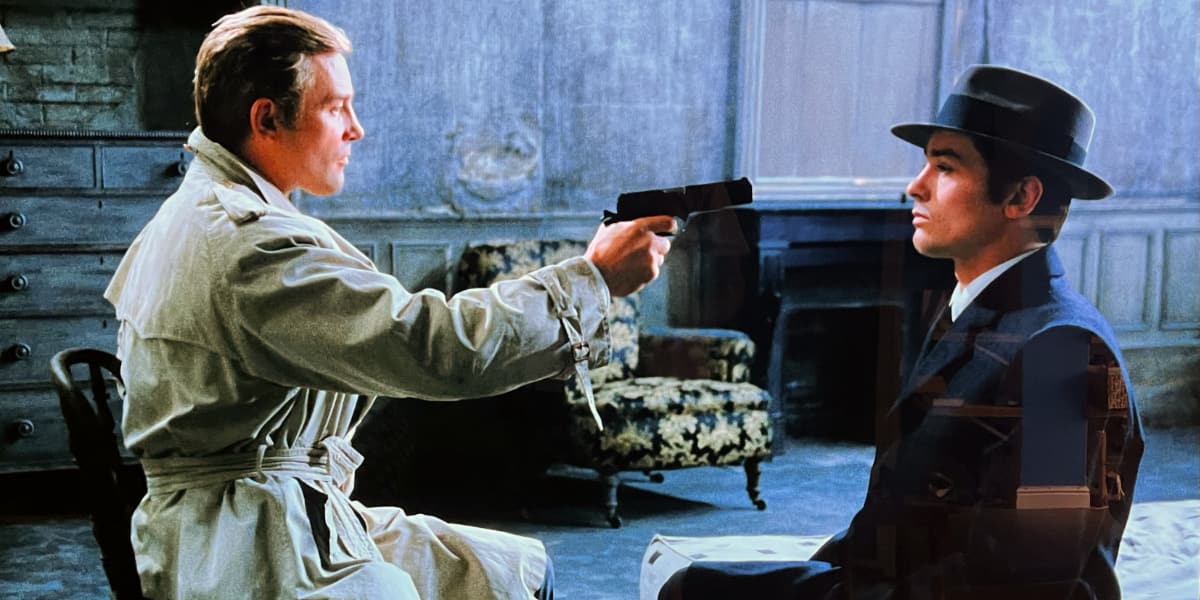

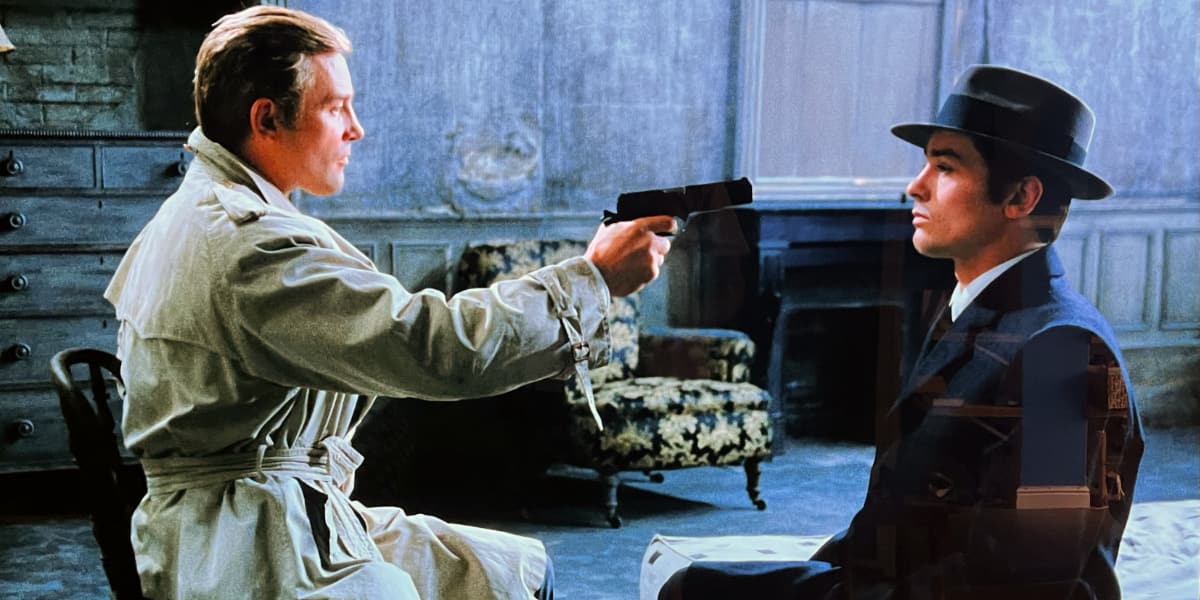

Director: Jean-Pierre Melville

Release year: 1967

Hitman Jef Costello takes a contract to kill a nightclub owner, but he is seen leaving the premises by several employees. Despite having a watertight alibi, the police superintendent doesn’t believe Costello and puts him under surveillance. Meanwhile, Costello’s employer is unhappy with the police involvement and the hitman has to find a way to get both parties off his back.

This feels like a seventies film, so it’s amazing to me that it was made in 1967, four years ahead of The French Connection, seven years before The Conversation, both of which take chunks of Le Samouraï’s DNA. Thinking about it, many films flow from here, including Ghost Dog, The American, Drive, The Killer... but then, Melville was heavily influenced by the gangster and noir films put out by Hollywood in the 40s and 50s, so it all goes around.

Alain Delon hardly moves his (beautiful) face, and the lack of emotion is deliberate, but it makes Costello a hard character to care about. The final scene is set up by a subtle display of remorse, but it wasn’t enough for me to feel much for him. Like Tati’s PlayTime, it is flawless in what it sets out to do, but doesn’t let you close to anyone. It’s technically perfect, but too cold for me to love.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 06 2025, 21:59

Director: Olivier Assayas

Release year: 1996

Hong Kong action star Maggie Cheung arrives in Paris to take the lead in a remake of a classic silent film, Les Vampires. The cast and crew are friendly, but Maggie is an outsider, and the group's conflicts and histories become increasingly pronounced as director René begins to realise the film is not working. Costume designer Zoé has a crush on Maggie, leading to further complications.

I thoroughly enjoyed this. Sometimes a film hits you just right. The camera weaves between the people working on the film set so that it feels like we are eavesdropping. Each character has some sort of grievance or flaw that plays out through the story. Maggie Cheung, playing herself, navigates with charm the petty politics and negative opinions of the film (and French cinema in general!), staying ever the professional as things falls apart around her.

René’s film is based on an infatuation with the idea of Maggie Cheung in a catsuit. That’s his entire energy for the film, and once she arrives and he gets what he wants, because the script isn’t good enough to sustain the idea, he has a nervous breakdown. As an actress, Maggie needs to understand what her director wants from her. Distraught at the creative failure of the film and not being able to help, Maggie wears the latex catsuit to sneak around her hotel, as if she is Irma Vep, her role in René’s vision. She steals a necklace—but was it a dream?

Unwilling to be replaced on the film, René makes a cut from the footage for the new director which is completely unhinged and wonderful. Perhaps Assayas is saying that French cinema has the possibility of being more adventurous, for all the film’s talk of it being stuck in the past. This was made in 1996, almost thirty years ago. It makes me want to find out what happened.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 09 2025, 19:52

Director: Jack Cardiff

Release year: 1968

I’m pleased with myself for seeing one of these #ArthouseSummer films in the cinema. The BFI South Bank is an amazing space, and it’s been several years since I’ve visited, so I’d forgotten how they have red curtains in NFT2 and how uncomfortable the seats are. Also, the weirdos.

A guy made a beeline for me in the foyer, an older fella getting far to close to me, and I had to do an unexpected pause and side step to get away from him. He then sat next to me in the film. My seat was booked hours earlier, but I can’t believe it was a coincidence, he must have crashed someone else’s seat. He struck up a conversation.

‘What brings you here to watch this film?’

I was confused. His emphasis was provocative. ‘Well, I’m writing some blog posts on arthouse films...’

‘You think this is an arthouse film?’

‘I haven’t seen it yet. I don’t know. I hope so.’

‘What are you writing?’

He didn’t seem to understand what a blog was, or pretended not to. ‘Posts on the internet.’

‘Well, whatever, you follow your dreams.’ The derision was floating around him in a cloud. ‘But it’s not good. It’s certainly not arthouse. It’s a piece of crap.’

‘I hope that’s not true. Look, please don’t spoil...’

‘And have you met her?’ He pointed towards the front of the cinema.

‘I don’t know who you’re pointing at...’ The penny dropped. ‘Marianne Faithfull? No, of course not. Have you?’ I knew the answer before I’d finished asking.

‘Yes. She was awful.’

At this point I exploded. ‘Are you going to spoil this for me? I’ve asked you not to. Are you going to be trouble? Because if you are I’ll have to move.’ I could sense the people around me listening to all this, but I was furious.

‘Okay, if you don’t want to talk, I’ll leave you alone.’ He pulled a large black backpack off the floor, heaved it onto the empty seat to his left, pulled out a large bag of sweets and started rustling them loudly.

Reader, I left the cinema. At the entrance, I spoke to the usher and he said just to sit anywhere once the film started, so I zipped down the front when he closed the rear doors and got an aisle seat, which was perfect. (I should say something about the film!)

Newly married Rebecca is given a motorbike as a wedding present by her sadistic lover, Daniel. Her husband, Raymond, allows her to keep it, and one morning she secretly sets off from their French home across the German border to visit Daniel in Heidelberg. We discover her story as part of her journey.

If I’d seen the film at home, I don’t think I’d have finished it, but there was something about it on the big screen that made it sing. It’s cheesy, the dialogue is often clunky, and Marianne Faithful gives an over-the-top performance, but damn it if I didn’t have a really good time. They showed the Alex Cox Moviedrome introduction to the film, and he’s pretty dismissive and snide about it, but I think he misses the swings director Jack Cardiff is going for.

It might be overgenerous to say the film is deliberately funny, but it’s definitely knowing in some of its humour, and it wrestles with ideas of marriage, monogamy, marrying young, what it means to be free, free love, types of masculinity, and indeed femininity... and it’s playful.

It’s not erotic, which was part of its marketing/mystique, because whenever there is sex, the screen pulsates with neon pinks and greens. It’s an experimental film, for sure, and the narrative unfolds in flashbacks and dream sequences to clever effect. It’s incredible, based on its current reputation as a bad cult film, that A Girl on a Motorcycle was the sixth most popular film on general release in 1968. It’s not a masterpiece, but it’s far more ambitious than most things that get made today.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 14 2025, 21:32

Director: Gaspar Noé

Release year: 2002

It’s been a couple of days since I watched this, but I needed time to let my thoughts percolate. Irréversible is infamous for the extended and brutally violent rape scene at its centre. The shock of it overwhelmed the critical thinking part of my brain, and it’s rare that I finish a film completely confused. Was it good, bad, clever, disgusting, homophobic, misogynistic, racist, or all of these things? What was Noé trying to achieve? I had to do some reading to help me work out what I thought.

I don’t think the plot of this movie can be spoiled. Noé’s trick is to play the scenes in reverse order, so we see the ending at the start. Its power comes from making the audience see the results of the choices made by the characters before knowing the reasons. The opening/finale is shown with a swirling camera that goes upside down, on its side, making us feel nauseous, while a rumbling drone constantly assaults our ears. We follow Marcus and Pierre into a version of hell. Marcus has lost his mind, but we don’t know why, and the violence he provokes is shocking. We are presented it all without context.

From here, we retreat through the evening. A couple, Alex and Marcus, go to a party with her ex-boyfriend Pierre. When Marcus takes cocaine and becomes aggressive, Alex leaves to go home, and in an underpass she is raped and beaten. Marcus wants revenge and sets out to find the rapist, finding the man in a gay sex club. Marcus gets into a fight, and in protecting Marcus from being raped, Pierre beats the man to death with a fire extinguisher. The police take them both away, but Alex’s rapist escapes justice.

Alex is an intelligent, independent woman, who bristles at Marcus’s view of her as somehow his property. She is surrounded by men who let her down through the evening. When she leaves the party, neither Marcus nor Pierre go with her. The police talk to Marcus and Pierre as if they are the victims of the crime. When Alex is taken to the hospital, instead of going in the ambulance, Marcus is tempted by local gangsters into seeking revenge, and Pierre goes with him. These are selfish decisions that leave Alex vulnerable and alone.

The further into the film we go, the closer we get to who Alex is, and the pace slows, there is more intimacy and tenderness, and the weight of what has happened to a woman with everything to live for hits home.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 17 2025, 09:53

Director: Michael Haneke

Release year: 2005

Another French classic from the early noughties that I’m only now getting around to. Georges and Anne, and their son, Pierrot, are living a comfortable middle class life in Paris when a VHS tape is left on their doorstep. The tape shows the outside of their house, with the family coming and going oblivious to the hidden camera. In the coming days, they receive more tapes, wrapped in violent child-like drawings, and Pierrot is sent one of the drawings in school. Increasingly freaked out, Georges suspects someone from his past, and tries to clear things up once and for all.

Haneke puts the bullish Georges in spaces where anyone else might feel threatened, and between the foreshadowing of the tapes’ content, Georges following the trail of clues, and the camera lingering over his shoulder and on possible antagonist faces, the suspense is palpable. The heart of the film emerges in Majid, who we learn was sent away to an orphanage when Majid’s Algerian parents, who worked on Georges’s parents’ estate, were killed in a 1961 massacre by the French National Police. Georges is convinced Majid wants revenge. Majid denies it, and we believe him, but unable to think of who else would send the tapes, Georges doubles down, eventually getting Majid and his son arrested.

Georges’s personal shame at his actions as a six-year-old is repressed so thoroughly that he cannot acknowledge the injustice he inflicted on Majid, and instead it makes him lash out and make things much worse. Haneke shows news footage in the background of many shots, and he seems to be saying Georges is a mirror of affluent French society, where the consequences of not acknowledging the horrors inflicted by their country’s power structures, especially on immigrants, leads to simmering resentments and social unrest.

We see a version of this in the UK now with Brexit, the scapegoating of immigrants, and Far Right groups rioting outside immigrant accommodation. Narratives of colonialism and British exceptionalism are still everywhere in right wing media, sickly nostalgic ideas kept alive by billionaires for profit.

Like Irréversible is famous for its violence, Caché (hidden, in English) is famous for the ambiguity of its ending. Certainly on first viewing, it isn’t clear who is making the tapes, and the final scene as the credits roll makes some suggestions, but the favourite take I read was that the hidden camera was God judging Georges for lack of empathy and remorse for his crimes. Psychologically, it could also be Georges’s own conscience, or unconscious, forcing him to face up to his past. Both work for me.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 24 2025, 17:56

Director: Bong Joon Ho

Release year: 2019

A family friend grants Ki-woo an opportunity to teach English to the daughter of a rich businessman, Mr Park. Ki-woo’s family is struggling to make ends meet, and they live in a basement flat in the poorest part of town. Once he’s secured the teaching job, Ki-woo and his family manipulate the Parks into hiring Ki-woo’s sister, father and mother, replacing all the existing staff. But the modernist house contains unexpected secrets, and their parasitic peace doesn’t last long.

I didn’t see this when it came out, and I can see why it won the main Oscars in 2020—it’s a masterpiece, and a rare hit film that takes a sledgehammer to the ideals of capitalism. The Park family live in a secluded house built by a famous architect in an exclusive part of Seoul high in the hills. When a storm sweeps through Seoul, the water flows downwards and floods the poor neighbourhoods with sewerage, and the rich don't even notice. Every relationship is transactional to the Park adults, although the younger children are shown as more innocent.

The Kim children are as corrupt as their parents, but no matter how hard they try, they can’t lift their family out of poverty. They are fighting a losing battle when they play by the rules. It’s hard not to cheer for them when they break rules to even the scales.

It all falls apart when they fail to show mercy to others in the same class as them. Once the workers stop helping each other, the rich win. The beautifully stark concrete house has a basement, and in the architect's paranoia, a basement far below that that’s more like a bunker. There are metaphors galore in this film. The wealth stone given to the Kims at the start of the story is one of the film’s best ironies.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

August 25 2025, 18:38

Director: Wong Kar-wai

Release year: 2000

In 1962 Hong Kong, two working couples, the Chans and the Chows, move in to neighbouring apartments in a house run by Mrs Suen. Both Mr Chow and Mrs Chan suspect their spouses are having an affair, and they begin their own relationship to work out what they should do next.

The opening act plays out through short scenes that drift together as time passes. We hear the voices, and see the backs of the heads, of the treacherous partners, but the camera cares about the wronged duo, who are luminous in every frame. The film is only ninety minutes long, and not a shot is wasted, with many like pieces of art in their own right.

Sometimes the strings will kick in, everything slows down, and either Mr Chow or Mrs Chan will glance at the other, or sadly smoke a cigarette, and we feel their longing in our bones. It’s a film about the loneliness of marriages that aren’t working. Mr Chow encourages Mrs Chan to help him write his serial, and the pair start a fruitful creative partnership in a rented room that’s spiced with romantic love, but the housekeeper, Mrs Suen, tightens the clamp of social norms on the burgeoning couple.

It’s a devastating film in the best way. I saw this in a cinema off Leicester Square when I moved to London in 2000, but I was too young to understand the depth of feeling in what was being shown on screen. I didn’t remember the final scenes in Cambodia at all, and I didn’t know Maggie Cheung played the heroine until the opening credits, which was a lovely unexpected link back to Irma Vep. Both Cheung and Tony Leung are sensational. This is one of my favourite discoveries of the year so far.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...

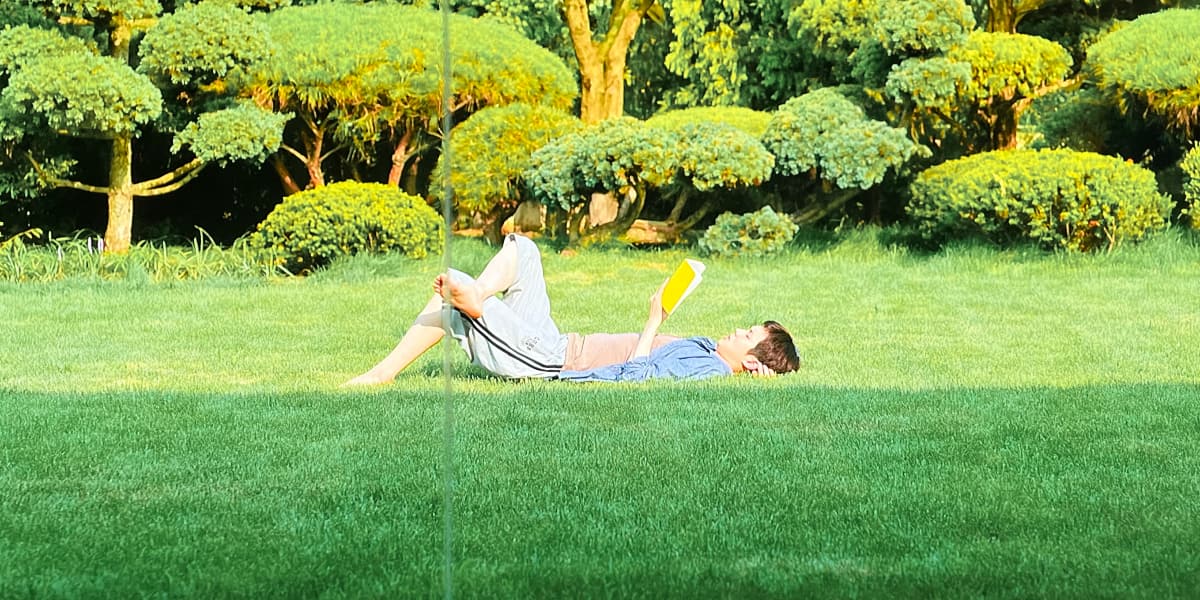

August 27 2025, 20:05

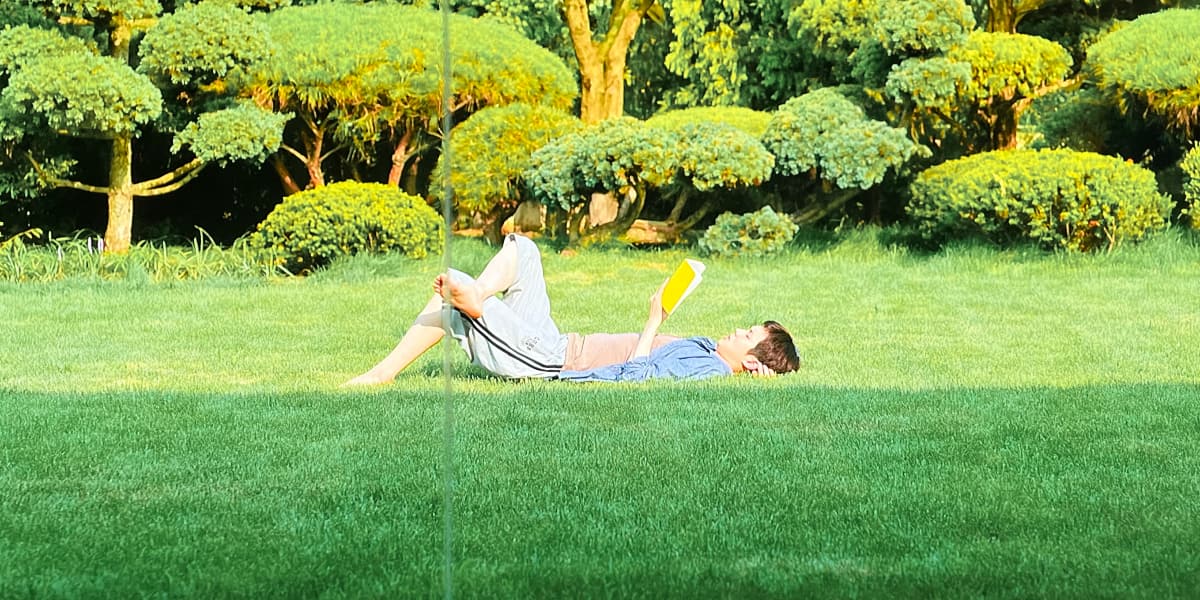

Director: Kazik Radwanski

Release year: 2024

Mara, a married creative writing professor, is surprised when Matt, a very close friend from her past that she no longer hears from, shows up at one of her lectures. They pick up their relationship while Matt is in town, leading to Matt driving Mara to a literary conference where the nature of their relationship is called into question.

This is an interesting counterpoint to In the Mood for Love where the almost-lovers strike out on different paths. Here, Mara and Matt are coming back together. Mara is married with a child, and Matt is perpetually single. Mara clearly loves her musician husband, but she doesn’t like music, and Matt offers conversation about literature and a playfulness with language that she can’t get in her marriage.

Mara has an idea for a collection of poems about a woman unconsciously acting out desires she’s unaware of, but is struggling to begin. Matt seems to be a successful and known novelist who is deliberately controversial to attract his audience. He’s extroverted, brash, slightly obnoxious, whereas Mara is unsure, introvert, and shy. Their opposite energies seem to be the source of their joy in each other’s company, and Matt is a catalyst to Mara’s hidden desires.

The camera is always close to both characters’ faces which allows us to follow every movement of an eyebrow and each mouth twitch as they hang out with each other in routine parts of their day. It isn’t clear if they were lovers in the past, or why they drifted apart, but for a brief time we observe them come alive in each other's company.

All films in 2025’s #ArthouseSummer...